জীর্ণ

Spaces of Separation

[2016 - Ongoing]Installation view, Delhi 2022

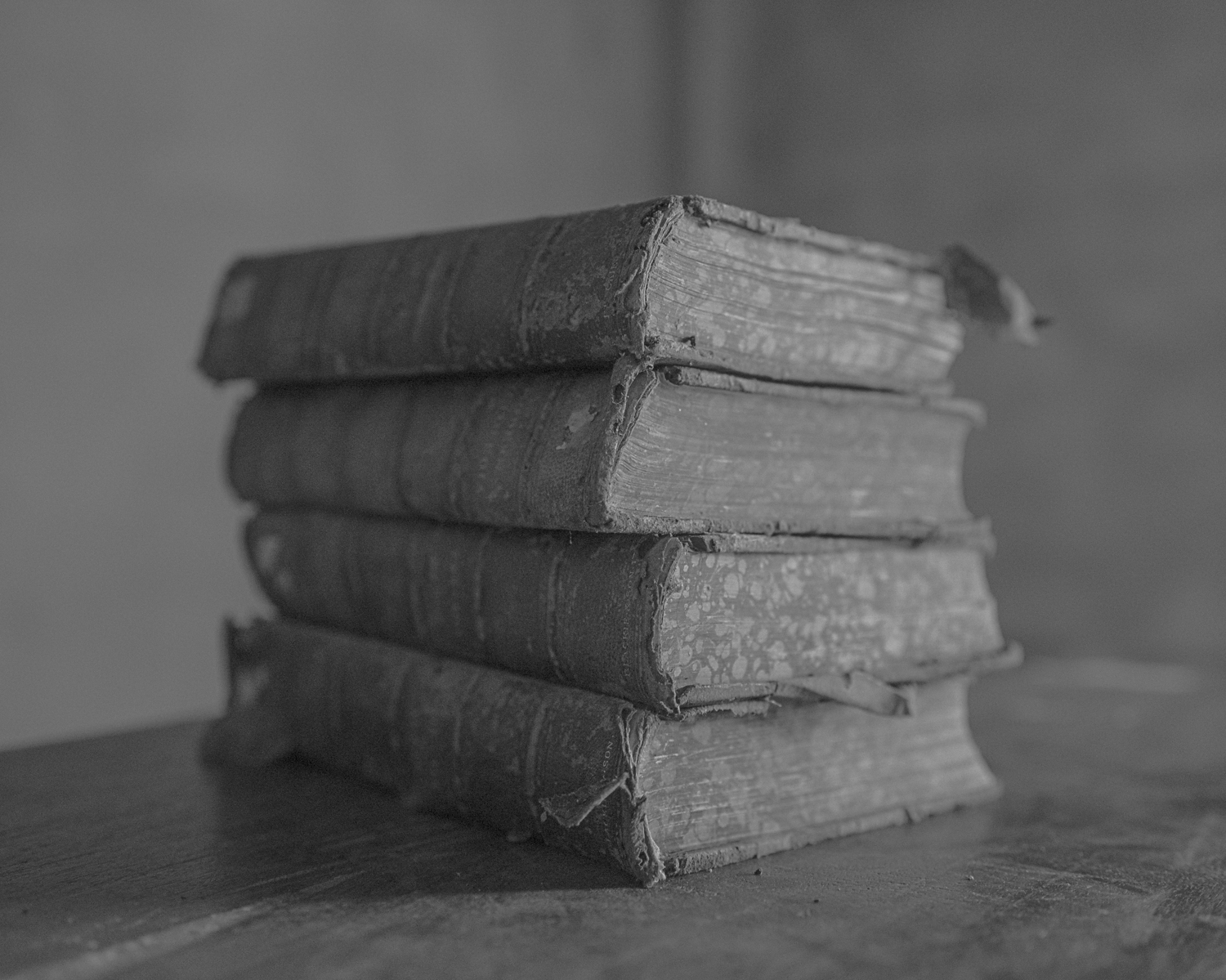

Jirno, speaks about the changing relationship between the time and land of pre-partition Bengal, observing the specific detail of abandoned jamindar houses, but in its speaking, it reminds the subtleties of transformation beyond its archaeological spasms; lights leaning into and casting out from colonial architectural ruins in a terrible, relentless brightness, with a stillness without relief, often fleeting and ending before change is completed. Digging personal memories becomes a reciprocal process while it engages and liberates the viewers of his images, who live with inescapable memories of the colonial past, personal and collective loss or belongingness, as well as with their imagined and imaginable escapes from it.

ELEGY

Essay by Sam Ishan

From 2016 onward, Sarker has been exploring and photographing abandoned feudal estates and decaying buildings previously owned by Hindu jamindars or landlords. The changing relationship between the land, its rulers and subjects as reflected in these regions is also a story of Bengal’s history: from the 1500s onward, the Mughal Empire established a system of apportioning tracts of land for the purposes of revenue collection, with the Muslim authorities receiving tax tributaries from conquered Hindu rajas. When British colonizers took over Bengal in the late 1700s, they entrenched this feudal structure with the Permanent Settlement, a system intended to extract large shares of revenue for the East India Company, while creating a small class of landed local aristocrats loyal to the British. It resulted, however, in the disenfranchisement of rural tenants, rifts between Muslim villagers and Hindu minority landlords, as well as unintended land speculation.

RUINS, 2016

Following the 1947 partition of India, Bengal was split, with predominantly Hindu West Bengal going to India, and predominantly Muslim East Bengal going to Pakistan. Renamed East Pakistan, East Bengal was to become the independent nation of Bangladesh following the Liberation War of 1971. Amidst the chaos of decolonisation and new nationhood, huge migrations were taking place: Hindus were leaving East Bengal for India, and in the same way, Muslims departed West Bengal. Those who were wealthiest and most well-connected—including landlords and large business owners—were the first to leave upon the loss of their political and social power. At the same time, a series of controversial laws dating from 1948, culminating in the Vested Property Act of 1974, allowed the confiscation of property from any groups declared “enemies of the state”. This led to the appropriation of many feudal properties and agricultural land that had belonged in the same family for generations, further spurring the departure of the jamindars. Sarker’s series JIRNO focuses on what remains of these abandoned landscapes and little-documented buildings, many of which have been taken over by nature and gradually enveloped into the daily life of the surrounding villages.

While contextualised by the events of the region, the work reflects broader philosophical ideas about the scale, directionality and universality of time. Buildings and structures, broken apart by the elements and enshrouded by tropical foliage. Despite the incompleteness of their forms, the architecture’s classical symmetry invites the eye to naturally trace lines where arches, columns and walls were once whole. Hybrid in their design and setting, they visualise specific ways that colonial and independence histories have marked the country, reflecting how the rise and fall of dominions can be read in the transformation of physical structures. With fields of view that move between wide vistas of land and sky, to intimate close-ups of minute detail and texture.

Sarker’s approach to making the work was a combination of the long exposures he is known for, and a methodical revisiting and photographing at very specific times of the day and in the year. This introduces another kind of time experience different from historical time, one that belongs instead to the cycles of the natural world, and includes the diurnal movement of day to night, and the rotation of seasons as they relate to agriculture. Such notions of cyclical time are shared and mythologised by many cultures, and suggests both the inexorable loss of time passing but also the possibilities presented by a kind of time that begins to end and ends to begin.